Teango

Triglot

Winner TAC 2010 & 2012

Senior Member

United States

teango.wordpress.comRegistered users can see my Skype Name

Joined 5548 days ago

2210 posts - 3734 votes

Speaks: English*, German, Russian

Studies: Hawaiian, French, Toki Pona

| Message 1 of 8 18 March 2011 at 7:19pm | IP Logged |

Automaticity is defined in Wikipedia as "the ability to do things without occupying the mind with the low-level details required, allowing it to become an automatic response pattern or habit. It is usually the result of learning, repetition, and practice."

I've often been curious about what goes on in the brain whilst progressing from learning completely new words and structures to relatively effortless fluency in communicating in a language. Is it simply a matter of strengthening neural data models and pathways over time, or does some of the data even get copied over to another parallel part of our brain at a later stage where all this automatic "magic" takes place?

[Whitaker, H. A. (1983). Towards a brain model of automatization: A short essay.]

Sadly, I don't know the answer to this question, but perhaps there are some other members here on the forum with a good wealth of experience and knowledge in the areas of neuropsychology or psycholinguistics who can offer up a possible answer...I think it's an interesting area.

And I have other questions about automaticity too. In particular, how long does this process generally take for people, and what lessons can we draw from this in the area of language learning and our expectations in developing basic fluency? Perhaps I can get a little further with these questions...

HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE TO FORM A HABIT?

Over the years, I've heard lots of different views on how long it takes to form or break a habit (usually during that first packed week down the gym in January :) ). The advice has ranged from repeating a given task every day for 21 days, up to gargantuan claims for the need to invest at least 10,000 hours.

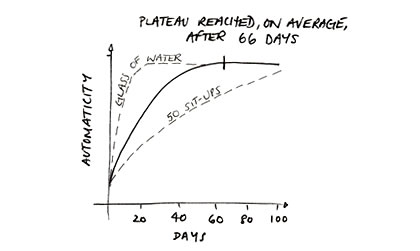

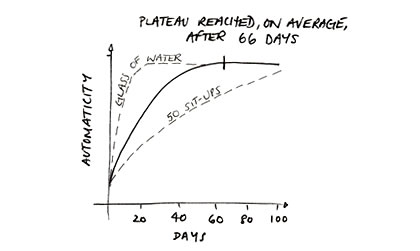

So after a little bit of research on the Net, I found the following article: How long to form a habit?. Summarising the article "How are habits formed: Modeling habit formation in the real world" published by Phillippa Lally et al in 2009, it explains that the length of time it takes to develop a habit really depends on what you're trying to automatise, the complexity and difficulty of the task involved, and how resistant you may be to forming habits anyway. This ranges in the study from 21 days for a simple task like drinking a glass of water after breakfast, to 254 days for more complex tasks (as I don't have access to the full paper, I can't say what this particular task might be but I'd certainly be interested to find out). When they averaged out all the data over 96 volunteers, the average time to form a habit worked out as approximately 2 months (66 days):

[Graph taken from the summary article: "How long to form a habit?".]

Of course this doesn't really tell us how long it takes to thoroughly learn a phrase or grammatical concept, and it probably varies considerably from individual to individual, which leaves us somewhere between "2 months" and guesswork on the basis of personal experience and others' accounts. It would be fascinating to read any other articles out there that have specifically focused on learning features in a new language to the point of automaticity, and if anyone can think of some that might shed further light on this question, please feel free do add them to this thread.

Here's the original abstract (Lally et al, 2009) for anyone who's interested:

"To investigate the process of habit formation in everyday life, 96 volunteers chose an eating, drinking or activity behaviour to carry out daily in the same context (for example ‘after breakfast’) for 12 weeks. They completed the self-report habit index (SRHI) each day and recorded whether they carried out the behaviour. The majority (82) of participants provided sufficient data for analysis, and increases in automaticity (calculated with a sub-set of SRHI items) were examined over the study period. Nonlinear regressions fitted an asymptotic curve to each individual's automaticity scores over the 84 days. The model fitted for 62 individuals, of whom 39 showed a good fit. Performing the behaviour more consistently was associated with better model fit. The time it took participants to reach 95% of their asymptote of automaticity ranged from 18 to 254 days; indicating considerable variation in how long it takes people to reach their limit of automaticity and highlighting that it can take a very long time. Missing one opportunity to perform the behaviour did not materially affect the habit formation process. With repetition of a behaviour in a consistent context, automaticity increases following an asymptotic curve which can be modeled at the individual level. "

HOW DOES THIS AFFECT MY EXPECTATIONS IN DEVELOPING BASIC FLUENCY?

One interesting discovery in this study is that once volunteers reached a 95% level of automaticity, following a generally asymptotic curve, their level didn't rise much higher and the graph simply plateaued for successive days. Perhaps this points to some kind of "epiphany" moment in terms of internalising a feature of the language? However, maybe we wouldn't even notice by this stage, finding ourselves too wrapped up in using the language rather than focusing on it as an outsider anymore?

Whichever the case, it appears that the process of digging deep roots into a language and attaining a decent level of fluency is composed of automatising thousands and thousands of smaller procedural and cognitive tasks that integrate together to make up the whole picture. This seems to happen through regular and consistent use of developing neural networks, particularly whilst learning through communicating with others and familiarising ourselves with the linguistic tools we have available in our everyday toolbox to solve challenges like reading a recipe or watching a movie.

This points to a less rigid concept of basic fluency that is less like reaching a stage in a marathon or collecting so many acorns, and more like forming an effective corporation consisting of thousands of smaller teams working together in general consensus towards a set of shared goals. Each one of these features in the language probably develops at a very different rate to others, and so as a whole, I picture fluency more as an organic and permeable flock of ideas or a variable sea of interconnected linguistic processes full of crashing waves, perplexing eddies and dead calms. By all accounts, developing and integrating all these processes can take a hell of a LONG time before they can be pieced together comfortably, and so we shouldn't really beat ourselves up for making thousands of tiny embarrassing mistakes along the way and taking time out regularly to let it all subconsciously sink in.

Edited by Teango on 18 March 2011 at 7:24pm

9 persons have voted this message useful

|

Arekkusu

Hexaglot

Senior Member

Canada

bit.ly/qc_10_lec�

Joined 5373 days ago

3971 posts - 7747 votes

Speaks: English, French*, GermanC1, Spanish, Japanese, Esperanto

Studies: Italian, Norwegian, Mandarin, Romanian, Estonian

| Message 2 of 8 18 March 2011 at 8:30pm | IP Logged |

It’s become increasingly clear to me lately that the key to fluency is the ability to access active mechanisms that help form habits. These mechanisms may be more or less conscious, but I believe successful language learners use active habit forming mechanisms.

Without active mechanisms, habits form on their own, but over a much longer period of time. Inevitably, before these habits are formed, a lot of information is lost, causing a serious waste of time and energy, and delays in attaining fluency.

If I simply try to remember a word, it goes into a part of my brain where I can access it with some effort for a short while, but I still need to create a habit to make it part of my easily and readily accessible vocabulary. I do that by deliberately repeating the word, using it in various sentences within diverse linguistic patterns, either to myself in exploratory mode, or in real life situations.

Generally, I have various habits forming simultaneously, and at different rates, many often intertwined within the same phrases. I have no idea how long it takes to create a habit, but it can definitely take less than 2 months. It can take a few days for sure, maybe less depending on how striking the information is. While the timing may depend on the complexity of the habit, or on the intricacy of its implications on entire sentences, I suppose it also depends on the importance I give it, thus affecting the energy I devote to forming the habit.

Other learners around me also form habits, but in what seems to be a much more passive – and less effective -- manner. It is also obvious that as they have no active habit forming mechanisms or very few of them, they have a much more difficult time changing the habits that need to be changed. As we learn a language, we constantly realize that previous habits were incorrect or incomplete and we need to be able to change them. If their habits are formed passively over time, the ability to correct or update habits is greatly hampered and general speaking improvements are much slower to appear.

Edited by Arekkusu on 18 March 2011 at 8:31pm

1 person has voted this message useful

|

Cainntear

Pentaglot

Senior Member

Scotland

linguafrankly.blogsp

Joined 6003 days ago

4399 posts - 7687 votes

Speaks: Lowland Scots, English*, French, Spanish, Scottish Gaelic

Studies: Catalan, Italian, German, Irish, Welsh

| Message 3 of 8 18 March 2011 at 9:24pm | IP Logged |

My view of this may be tainted by studying fairly simplistic models of thought in undergrad artificial intelligence, but here's my tuppence worth.

It feels to me like there's two different mechanisms involved.

As an absolute beginner in language (French) I had to think things out -- I relied on conscious knowledge to construct the sentence.

After a while, I started to notice that while I was thinking about how to form the correct sentence, there was a fully formed sentence appearing in parallel. It seemed like that voice had been there for a while, but I was just thinking too hard to notice it.

I started trusting that instinct more, but I was always thinking too, and the "conscious language thought" would spot any mistakes in the "instinctual language thought" (see also the monitor hypothesis).

It got to the point where I became aware that I was holding back the instinctual sentence until I had formed the conscious sentence, which I realised was slowing me down. One leap of faith and then... I was talking the language.

Well, that's a bit of an exaggeration, because I still had to go through the same process when I learned new pieces of grammar....

The idea of a levelling out at 95% proficiency makes sense to me, because when my instinctual speech is faster than my conscious monitor, my monitor isn't really much use any more!

Anyhow, I look on this from a connectionist point of view.

Connectionism models the brain as a mesh of interconnected mathematical units. In very rough terms, a neuron just carries out a simple sum and triggers a yes or no signal.

Connectionist neural nets are trained simply by giving a set of inputs and the desired output. The net then adjusts the calculations made at individual neurons until it creates the correct output for the given input.

As you give the net more and more pairs of input and output, the net naturally makes its own generalisations about input. With a big enough network and a fully representative set of training data, you could theoretically train a computer to do absolutely anything.

For the brain, consciously doing stuff is quite slow and inefficient, so it always tries to find an easier way. Not an easier way to do it consciously, a completely different way to do it, automatically. It can compare the inputs and outputs (including intermediate outputs) of the conscious process to its best guess at an instinctive, automatic process and adjust its model when it spots a mistake.

What are the inputs and outputs in language?

The obvious answer is hearing and speaking (and/or reading and writing), but that misses the point of language as a mental process, so I'll rephrase the question:

What are the inputs and outputs of speaking a sentence?

The input is your intended meaning -- what you want to say. Your output is a sentence.

What are the inputs and outputs of hearing a sentence?

The input is the sentence. The output is a reconstructed intended meaning -- what the speaker wanted to say.

You cannot train a neural net without both the inputs and outputs. This is why I think translation as a method of learning isn't the evil thing many people make it out to be.

If you tell me something in my native language, I know what it means effortlessly. If I then translate it correctly, I have both meaning and form and I can tie the two together.

If you ask me a question in a language I don't know well yet, I can give you an answer that will satisfy you as a teacher, but without really having a strong intended meaning -- I say it because "it's right", not because I want to say it. If I don't want to say it, it's not speaking, it's parrotting.

4 persons have voted this message useful

|

BartoG

Diglot

Senior Member

United States

confession

Joined 5439 days ago

292 posts - 818 votes

Speaks: English*, French

Studies: Italian, Spanish, Latin, Uzbek

| Message 4 of 8 19 March 2011 at 11:06pm | IP Logged |

In the new book, Moonwalking with Einstein, Joshua Foer gets at this question in discussing two people whose brain damage prevents short term memories from entering long term memory. In one case, a person was taught a skill (using a mirror to make tracings). Every time he was asked to do the activity, he was sure he'd never done it before. But by the thirtieth day, he was doing quite well on the first try and astonished at how quickly he had picked it up (in his perception). In a second case, a person was given a list of words to work through. While he had no recollection of the words, or indeed of having done an exercise with words, when these words, interspersed with others, were flashed on a computer screen, sensors following his eye movements showed that he read the words from the list considerably faster.

The ability to consciously retrieve a memory and convert it to information you can verbalize - i.e. data or a narrative sequence - is known as declarative memory. But there are other kinds of memory. Learning things consciously gives you the information to work at the process (poorly) until it becomes "second nature" (why not first nature?). Retrieving things consciously enables you to re-enter a sequence where you're doing things unconsciously. For example, when you learn to add, you're consciously taught. And if you lose track while you're doing a sum, you may remind yourself consciously, "Carry the two." But if you did mathematics fully by conscious application of consciously remembered rules you'd need to set aside an afternoon to double-check your grocery receipt. Most of math is done unconsciously.

With language, we like to think we're learning things - vocabulary, grammar rules, etc. But we don't use our declarative memory for language. We use language for our declarative memory! Like mathematics, it's another way - a far more common way! - of organizing our thoughts for the purpose of declaring them to others. And so the point where you're using a language well is that point when you stop thinking about it.

There is one very big implication here for language learners.

Teango wrote:

| [A]ttaining a decent level of fluency is composed of automatising thousands and thousands of smaller procedural and cognitive tasks that integrate together to make up the whole picture. |

|

|

Your keywords are procedure and task. It's not how many words you "know," it's how many words come automatically to mind. It's not how many tenses you "know," it's whether you reflexively chose the right form. Very often, in language learning, we get caught up in learning things at the level of declarative memory. For one thing, we can only consciously count up what we consciously know. For another, we confuse knowing something with knowing how to make use of it. But if you want to get fluent in a language, you don't need automaticity for remembering words, you need automaticity for speaking. That means your practice activities need to focus not on memory retrieval, but on speech production.

I realize I've covered some ground from earlier comments, but I think drawing this declarative memory/other memory distinction is of use to make sure we try to develop the kind of memory we really need for language learning. Because if the experimental evidence says that a heavy-duty amnesiac whose ability to remember new things is gone can still show an automatic memory for words if prompted in a different way, then getting hung up on burnishing our declarative memories is likely not the key to developing automaticity in our language learning.

2 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6695 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 5 of 8 20 March 2011 at 6:18pm | IP Logged |

Cainntear wrote:

It feels to me like there's two different mechanisms involved.

As an absolute beginner in language (French) I had to think things out -- I relied on conscious knowledge to construct the sentence.

After a while, I started to notice that while I was thinking about how to form the correct sentence, there was a fully formed sentence appearing in parallel. It seemed like that voice had been there for a while, but I was just thinking too hard to notice it.. |

|

|

This is a very interesting statement, and one I can recognize from myself. And of course I tend to formulate my own perception of it in terms of learning strategies.

I have written about intensive and extensive strategies and activites again and again, mostly - but not exclusively - in the realm of passive learning. And I have stated that intensive activities are most important in the beginning, whereas the scales tip more and more in the favor of extensive activities the further you progress in your learning process. And the reason that this happens is mainly that more and more of the knowledge you get through intensive activities is covered by automatic and even subconscious mechanisms.

One example of this is that you don't have to run through a conjugation table to find an ending and construct a certain form of a word - you have seen this form so often that this particular form is stored as an individual item. Other examples are the influence of one sound on surrounding sounds, the choice of preposition after a noun or verb and the choice of case after a preposition. But even though these individualized reflexes are the end goal they don't have to be absorbed as single items, which would last forever. Tables and list of rules are there to show you where all those scattered pieces of information belong.

In the beginning of a language study there is basically only one active extensive activity available for you: parroting. You can hear an expression (in a situation where you can guess the meaning), and then you repeat it. Actually you don't even need you left brain with its language centers for this - the right brain can store this kind of unreflected fragments. The intensive language production starts already when you make the first minimal change - you have to know something about the mechanism of the phrase to make that change. And unless you continue along the parrot trail most or your active language production will consist of constructed utterances for a very long time.

But lo and behold, at a certain point you may experience the same thing as Cainntear, namely that some little gnomon in the back of your mind will start making sentences on his/her own, and then you can start your extensive language production career.

The problem is that this is more likely to happen if you do a lot of language production the hard way first. For those of us who rarely speak in foreign languages at home this can partly be solved through silent thinking and (for the more energetic ones) by speaking to yourself - I remember an excellent advice about pretending that you speak into a mobile phone, if you are to shy to walk around speaking to nobody in public. However I personally mostly stick to silent thinking.

Nevertheless I have found one trick that might be worth exploiting for others: I listen to something on TV or on the internet in a language I know fairly well, and then I make a simultaneous translation to a related weak language on the fly. Of course it will be totally rubbish in the beginning, but just having to hammer through something like a translation at the speed of a native speaker will mean that I don't have time to construct anything - and then the little lurking gnomon has the chance to appear without any interference from my internal schoolmaster. And with time the little fellah may even be able to speak in somewhat sounding like the real thing - but only because the systematic part of me constantly feeds him with information about the language in question.

And no, I don't feel like a victim of multiple personality disorder.

Edited by Iversen on 20 March 2011 at 6:32pm

4 persons have voted this message useful

|

Arekkusu

Hexaglot

Senior Member

Canada

bit.ly/qc_10_lec�

Joined 5373 days ago

3971 posts - 7747 votes

Speaks: English, French*, GermanC1, Spanish, Japanese, Esperanto

Studies: Italian, Norwegian, Mandarin, Romanian, Estonian

| Message 6 of 8 22 March 2011 at 3:57pm | IP Logged |

I'm surprised this thread has not generated more discussion.

I've come to consider automaticity-building strategies to be the single most important part in the successes I've had with languages.

Surely other people have an opinion on the matter.

1 person has voted this message useful

|

CaucusWolf

Senior Member

United States

Joined 5264 days ago

191 posts - 234 votes

Speaks: English*

Studies: Arabic (Written), Japanese

| Message 7 of 8 23 March 2011 at 2:55am | IP Logged |

Iversen wrote:

Nevertheless I have found one trick that might be worth exploiting for others: I listen to something on TV or on the internet in a language I know fairly well, and then I make a simultaneous translation to a related weak language on the fly. Of course it will be totally rubbish in the beginning, but just having to hammer through something like a translation at the speed of a native speaker will mean that I don't have time to construct anything - and then the little lurking gnomon has the chance to appear without any interference from my internal schoolmaster. And with time the little fellah may even be able to speak in somewhat sounding like the real thing - but only because the systematic part of me constantly feeds him with information about the language in question.

And no, I don't feel like a victim of multiple personality disorder.

|

|

|

I've noticed myself doing this alot when reading or listening to English at random times. I'll read and all of a sudden start translating in Arabic and wont be able to stop myself from doing it.(unless there's a word I don't know an equivalent of.) Now I'll even translate spoken sentences or words if I don't know a similar word to translate to in Arabic.

All of this seems to be automatic and is totally unintentional. I guess this is what happens when you're studying for 4 or more hours a day on a particular(excluding weekends) language for over a year.

1 person has voted this message useful

|

yourvietnamese

Newbie

Singapore

yourvietnamese.com

Joined 4972 days ago

9 posts - 6 votes

Speaks: English

| Message 8 of 8 15 April 2011 at 6:49am | IP Logged |

Arekkusu wrote:

I'm surprised this thread has not generated more discussion.

I've come to consider automaticity-building strategies to be the single most important part in the successes I've had with languages.

Surely other people have an opinion on the matter. |

|

|

I absolutely agree with you that building habit is the key for learning languages or just about any other skills.

Part of the reason why I think this works is because we need constant input in the target language: we need to speak, to listen, to read, to write to master the language. Or else it'd get "rusty".

Thanks for a sharing a great thought.

1 person has voted this message useful

|