16 messages over 2 pages: 1 2 Next >>

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 1 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:09pm | IP Logged |

This thread is part of a series of guides to langage learning, and no. 1 thread in this series is found HERE. The necessary caveats can also be seen there.

How many words do you need to learn?

Quote from the first post, written by Administrator, in the thread How many words do you need to learn?, 24 March 2005:

I have a file of lexemes in Russian sorted by frequency. Lexemes are 'unique' words, that is for instance 'to be' instead of counting 'is' 'was' 'are' are a different word each time.

(...)

The result is that:

the 75 most common words make up 40% of occurences

the 200 most common words make up 50% of occurences

the 524 most common words make up 60% of occurences

the 1257 most common words make up 70% of occurences

the 2925 most common words make up 80% of occurences

the 7444 most common words make up 90% of occurences

the 13374 most common words make up 95% of occurences

the 25508 most common words make up 99% of occurences

(end of quote)

ProfArguelles (in the same thread):

The maddening thing about these numbers and statistics is that they are impossible to pin down precisely and thus they vary from source to source. The rounded numbers that I use to explain this to my students I usually write in a bull's eye target on the whiteboard:

250 words constitute the essential core of a language, those without which you cannot construct any sentence.

750 words constitute those that are used every single day by every person who speaks the language.

2500 words constitute those that should enable you to express everything you could possibly want to say, albeit often by awkward circumlocutions.

5000 words constitute the active vocabulary of native speakers without higher education.

10,000 words constitute the active vocabulary of native speakers with higher education.

20,000 words constitute what you need to recognize passively in order to read, understand, and enjoy a work of literature such as a novel by a notable author.

(end of quote)

My own contribution to that thread, p. 6 (25 January 2007):

… the main obstacle to reading and listening fluently is lack of vocabulary. For some people it may be difficult to remember words without contexts, but my own experience with wordlists have shown me that I can learn words much faster by using structured methods. By this I mean that it is not enough just to read a long list of words with translation and maybe repeating each combination fifty times. You can use different methods, but writing the lists in small chunks and memorizing, immediately followed by control in both directions, does the trick for me, and then afterwards I use the same repetition techniques that I would use on passive words to make the words stick, - in my case it is dictionary checks, but flashcards is a viable alternative. I have written extensively about that in other threads.

When you first have the words inside your head, reading and listening is necessary to get the nuances, construction possibilities and idiomatic uses, but all that is only possible when you already have a nodding acquaintance with the word in question.

The funny thing is that for once it is a thing that is measurable: I originally started my concentrated work on dictionaries and word lists because I just wanted to known my passive vocabulary in Romanian. But then I discovered that my vocabulary thundered upwards by relearning those half forgotten words. Later I experimented with techniques to learn new words, and now I can not only feel, but even count the effects. And reading/listening has become much more pleasurable now that I can do it without looking up ten words in each sentence. Now I can focus on syntax and idiomatics.

10000 active, 20000 passive words would be a good estimate of where you are leaving basic fluency and moving towards advanced fluency, but of course only in conjunction with a firm grasp on grammar and idiomatics, plus easy active use of the language in question (at least if you want to claim active fluency, not only passive fluency). And to get there dictionaries, word lists and flashcards are not enough, - you have to meet real living language (and produce it yourself).

(end of quote)

Quote from How many words do you learn per day?, 05 September 2009:

Not to discourage anybody, but take a small dictionary with about 10-15000 words and try to look up every unknown word from some ordinary text in a language you don't already know too well. How many did you find? My own experience with a Greek scientific magazine is maybe half the words I didn't know weren't included in the dictionary either - so apparently even 10-15000 words isn't enough. And here I'm not talking about specific scientific terms, because they often are international and therefore not among those I had to look up. So a daily word intake of at least 100 words is not only possible, but it really is what you MUST aim for if you want to learn a language within a reasonable time (but of course this will be more difficult if it isn't closely related to something you already know). Good luck!

Edited by Iversen on 17 September 2009 at 10:59am

25 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 2 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:10pm | IP Logged |

Learning words from context

Quote from the thread Strategy: Learn 600 words a week, 09 October 2007

The assumption behind wordlists, flashcards and things like that is not that two languages are 100% connected on a word to word basis, - and you would be hard pressed to find anybody who seriously believe that. The purpose behind such systematic learning tools is to familiarize people with enough words to get through genuine texts without stumbling over unknown words all the time. The meaning that is associated with a given foreign word is for practical reasons its approximate translation into another language, which may or may not be the native language of the student. But it could also be a drawing or an explanation in the target language or a translation into a third language if there is suitable term there. The important thing that you get just enough feeling for the meaning of the word to understand it when you meet it in 'real living language', and having a dictionary translation (with examples, if necessary) as a background is much safer than believing that you know all about it just from seeing it once in context. Many things in language are idiomatic, but it doesn't imply that languages are purely idiomatic. It is still valid to note that a English horse is the same as a French cheval, even there are idiomatic expressions with both words that can't be translated directly.

My position is - and will continue to be - that languages are not purely idiomatic, and therefore it is perfectly legitimate to use tools that ultimately are based on translations. In fact, I find it strange that there are people who are unable to or refuse to use such tools. But we are clearly different, and everybody should use the methods that work for him or her. In the end we all expect to get to a situation where we use the target languages without translating mentally, - we just can't agree on how to get there.

Quote from the thread How many words do you need to learn?, 25 January 2007:

Let me add to this old text that I remain sceptical about learning words purely from context. If I meet a word in a certain context then I may feel that I can guess the meaning, - or at least determine its category. For instance I might suspect that "usignolo " is some kind of bird in Italian, and I might also be able to guess that it is the same as a "Rossignol" in French. But I would feel much more certain if I saw in a dictionary that it is a nightingale ("nattergal" in Danish). And I would understand the Italian text much better if I already knew this when I saw the word there. Now the name of a bird is something very concrete, but the principle is valid also for more abstract words and words with more meanings.

Even the possession of a translation can't give the same sense of security as a simple look in a good dictionary, because the translation is targeted towards one text, while the dictionary is intended to be used more generally - and if it is a good dictionary it will also list other meanings of the word. Of course I don't expect that you learn 20.000 Italian words before you read a single line in the language, but getting a fruitful alternation between the use of dictionaries and similar sources and the use of genuine texts gives in my opinion a much better base for learning foreign words than guesswork based only on those texts.

Edited by Iversen on 17 September 2009 at 10:57am

14 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 3 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:11pm | IP Logged |

Word lists

("Iversen's method")

A word list is in its most common form a list of words in a target language with one translation of each word into another language, here called the base language. However you can use short idiomatic word combinations instead of single words, or you can give more than one translation into the base language, and it will still be a word list. You can also add short morphological annotations, but there isn't room for examples or long comments in a typical word list. Lists of complete sentences with translations are not word lists.

There are also word lists with just one language (frequency lists) or with more than two languages. The so called Swadesh lists (named after Morris Swadesh) contain corresponding lexical items from a number of languages, typical 100 or 200 items chosen among the most common words. Both these lists can be valuable for a language learner who wants to make sure that s(he) covers the basic vocabulary of a target language.

Dictionaries can be seen as sophisticated word lists, where the target items (lexemes) are put in alphabetical order, and where the semantic span of each lexeme is illustrated through the use of multiple translations, explanations and examples, sometimes even quotes. In addition good dictionaries give morphological information about both the target language and the base language words. However the amount of information in dictionaries varies, and the most basic pocket dictionaries are hardly more than alphabetized word lists.

Using word lists

The most conspicuous use of word lists is the one in text books for language learners, where the new words in each lesson are summarized with their translations. However they are also an important element of language guides used by tourists who don't intend to learn the language of their destination, but who need to communicate with local people. In both cases the need to cover all possible meanings of each foreign word is minimized because only some of them are relevant in the context, - in contrast, a dictionary should ideally cover as much ground as possible because the context is unknown.

Using word lists outside those situations has been frowned upon for several reasons which will be discussed below. However they can be a valuable tool in the acquisition of vocabulary, together with other systems such as flash cards. The method that is described below was introduced by Iversen in the how-to-learn-all-languages forum as a refinement of the simple word lists, and it was invented because he found that simple word lists weren't effective when used in isolation (except for recuperation of half forgotten vocabulary).

Methodology

One basic tenet of the method is that words shouldn't be learnt one by one, but in blocks of 5-7 words. The reason is that being able to stop thinking about a word and yet being able to retrieve it later is an essential part of learning it, and therefore it should be trained already while learning the word in the first place. Normally people will learn a word and its translation by repetition: cheval horse, cheval horse, cheval hose... (or horse cheval cheval cheval cheval....), or maybe they will try to use puns or visual imagery to remember it. These techniques are still the ones to use with each word pair, but the new thing is the requirement that you learn a whole block of words in one go. The number seven has been chosen because most people have an immediate memory span of this size. However with a new language where you have problems even to pronounce the words or with very complicated words you may have to settle for 5 or even 4 words, - but not less than that.

Another basic tenet is that you should learn the target language words with their translations first, but immediately after you should practice the opposite connection: from base language to target language. And a third important tenet is that you MUST do at least one repetition round later, preferable more than one. Without this repetition your chances of keeping the words in your long time memory will be dramatically reduced.

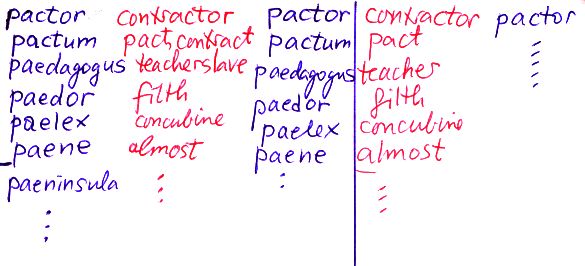

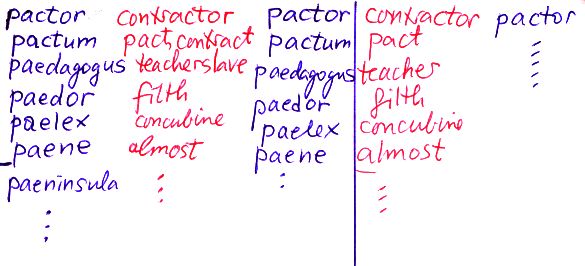

This is the practical method: Take a sheet of paper and fold it once (a normal sheet of paper is too cumbersome, and besides you need too many words to fill it out). Make three columns. Now take 5-7 words from your source and write them under each other in the leftmost third of the left column. Don't write their translations yet, but use any method in your book to memorize the meanings of these 5-7 words (repetition, associations), - if you want to scribble something then use a separate sheet. Only write the translations when you are confident that you can write translations for all the words in one go. And use a different color for the translations because this will make it easier to take a selective glance at your lists later. If you do fail one item then look it up in your source, but wait as long as possible to write it down - postponement is part of the process that forces your brain to move the word into longterm memory.

OK, now study these words and make sure that you remember all the target language words that correspond to the translations. When you are confident that you know the original target words for every single translation you cover the target column and 'reconstruct' its content from the translations. Once again: If you do fail one item then look it up in your source, but wait as long as possible to write it down (for instance you could do it together with the next block) - the postponement is your guarantee that you can recall the word instead of just keeping it in your mind. So now you have three columns inside the leftmost column, and you are ready to proceed to the next block of 5-7 words. Continue this process until the column is full.

There isn't room for long expressions, but you can of course choose short word combinations instead of single words. It may also be worth adding a few morphological annotations, but this will vary with the language. For instance you could put a marker for femininum or neuter at the relevant nouns in a German wordlist, - but leave out masculinum because most nouns are masculine and you need only to mark those that aren't. Likewise it might be a good idea to indicate the consonant changes used for making aorists in Modern Greek, but only when they aren't self evident. In Russian you should always try to learn both the imperfective and the corresponding perfective verb while you are at it, and so forth. You can't and you shouldn't try to cram everything into your word lists, but try to find out was is really necessary and skip the details and the obvious.

Sources

You can get your words from several kinds of sources. When you are a newbie you will probably have to look up many words in anything you read in the target language. If you write down the words you look up then these informal notes could be an excellent source, - even more so because you have a context here, and it would be a reasonable assumption that words you already have met in your reading materials stand a good chance of turning up again and again in other texts. Later, when you already have learned a lot of words, you can try to use dictionaries as a source. This is not advisable for newbies because most of the unknown words for them just are meaningless noise, but when you already know part of the vocabulary of the language (and have seen, but forgotten countless words) chances are that even new unknown words somehow strike a chord in you, and then it will be much easier to remember them. You can use both target language dictionaries and base language dictionaries, - or best: do both types and find out what functions best for you.

Repetition (added aug. 2012)

As mentioned above repetition is an indispensable part of the process, and it should be done later the same day, but better one day later. The repetition can of course be done in several ways, but these three are the main ones:

1) check the words in the original text (if that isn't a dictionary)

2) make two extra columns, one for the translations and one for the original words. Write the translations blockwise and don't write the original words in a block before you can write them all.

3) cover the translations in the original word list, take a new sheet and copy the foreign words one by one to this sheet. If you are in doubt about a word you slide the cover down to check the translation and copy it to the repetition sheet (as a sepearat column or just as a comment).

This setup corresponds with repetition method 2) above.

The combined layout was the one I developed when I had used three-column wordlists for a year or so and found out that I had a tendency to postpone the revision - having it on the same sheet as the original list would show me exactly how far I had done the revision, and I would only have to rummage around with one sheet. And for wordlists based on dictionaries or premade wordlists (for instance from grammars) it is still the best layout. But I have since come to the conclusion that it isn't the most logical way to do the revision for wordlists based on texts, especially those which I had studied intensively and maybe even copied by hand. Here the smart way to work is to go back to the original text (or the copy) and read it slowly and attentively while asking myself if I know really understood each and every word. I had put a number of words on a wordlist because I didn't know them so if I now could understand without problems them in the context then I would clearly have learnt something - and I would also get the satisfaction of being able to read at least one text freely in the target language. If a certain word still didn't appear as crystal clear to me then it would just have to go into my next wordlist for that language. So now I have dropped the repetition columns for text based wordlists.

Then what about later repetitions? After all, flash cards, anki and goldlists all operate with later repetitions. Personally I believe more in doing a proper job in the first round (where there actually are several 'micro-repetitions' involved), but it may still be worth once in a while to peruse an old wordlist. My advice here is: write the foreign words down, but only with translation if you feel that a certain word isn't absolutely wellknown - which will happen with time no matter which technique you have used. The format doesn't matter, but writing is better than just reading - and paradoxically it will also feel more relaxed because you don't have to concentrate as hard when you have something concrete like pencil and paper to work with.

Memorization techniques and annotations (new)

When you write the words in a word list you shouldn't aim for completeness. If a word has many meanings then you may choose 1 or 2 among them, but filling up the base language column with all sorts of special meanings is not only unaesthetic, but it will also hinder your memorization. Learn the core meaning(s), then the rest are usually derived from it and you can deal with them later. Any technique that you would use to remember one word is of course valid: if you have a 'funny association' then OK (but take care that you don't spend all your time inventing such associations), images are also OK and associattions to other words in the same or other languages are OK. The essential thing in the kind of wordlist I propose here is not how you do the actual memorization, but that you are forced to do it several times in a row because of the use of groups, and that you train the recall mechanism both ways.

It will sometimes be a good idea to include simple morphological or syntactical indications. For instance English preposition with verbs, because you cannot predict them. Such combinations therefore should be learnt as unities. For the same reason I personally always learn Russian verbs in pairs, i.e. an imperfective and the corresponding perfective verb(s) together. With strong verbs in Germanic languages you can indicate the past tense vowel (strong verbs change this), and likewise you can indicate what the aorist of Modern Greek verbs look like - mostly one consonant is enough. There is one little trick you should notice: if you take a case like gender i German, then you have to learn it with each noun because the rules are complicated and there are too many exceptions. However most nouns are masculine, so it is enough to mark the gender at those that are feminine or neuter, preferably with a graphical sign (as usual Venus for femininum, and I use a circle with an X over to mark the neutrum). This is a general rule: don't mark things that are obvious.

Arguments against using word lists

Finally: which are the arguments against the methodical use of word lists in vocabulary learning?

One argument has been that languages are essentially idiomatic, and that learning single words therefore is worthless if not downright detrimental. There is a number of very common words in any language where word lists aren't the best method because they have too many grammatical and idiomatic quirks, - however you will meet these words so often that you will learn them even without the help of word lists. On the other hand most words have a welldefined semantic core use (or a limited number of well defined meanings), and for these words the word list method is a fast and reliable way to learn the basics.

Another argument is that some people need a context to remember words. For these people the solution is to use word lists based on words culled from the books they read.

A third argument is that the use of translations should be avoided at any costs because you should avoid coming in the situation that you formulate all your thoughts in your native language and then translate them into the target language. But this argument is erroneous: the more words you know the smaller the risk that your attempts to think and talk in the target language fail so that you are forced to think in your native language.

A fourth argument: word lists is a method based entirely on written materials, and many people need to hear words to remember them. This problem is more difficult to solve, - you could in principle have lists where the target words were given entirely as sounds (or as sounds with undertexts), but you would have serious problems finding such lists or making them yourself. But listening to isolated spoken words is in itself a dubious procedure because you hear an artificial pronunciation and not the one used in ordinary speech. However the same argument could be raised against any other use of written sources, except maybe listening-reading techniques.

A fifth argument: there is a motivational problem insofar that many people prefer learning languages in a social context, and working with word lists is normally a solitary occupation. It might be possible to invent a game between several persons based upon word lists, but it would not be more attractive or effective than the forced dialogs and drills used in normal language teaching

UPDATE ON REPETITION METHODS (aug.2014):

I have experimented with three different repetition methods since I designed the original three column format for the original wordlist: checking the source text, making a simplified wordlist (as described above) and using a control format with basically one column plus a column for comments.

One way of checking that you remember the words on a given list is to go back to the text from which you took the words in the first place (which obviously isn't realistic with a dictionary). If you go through the text and acribically check whether you understand each and every word, you can jot down the words where you have any kind of doubt and relearn them through wordlists or some other method. I practice I have however discovered that this exercise unconsciously made me read the text extensively because I now understood it much better, and then having to write anything down became a chore. So it is practicable, but not as unproblematic as you might assume.

To second method is the one described above: make a wordlist with one column for the translations and then fill out another with the original foreign words, dividing them into 5-7 word blocks as usual. This is probably the most efficient method, but can become somewhat tedious.

So for quite some time now I have used a third method: I simply cover up the translations column in the original list and copy one word after the other to another sheet of paper. If I'm in any kind of doubt about a word I slide the cover downwards and copy the translation to the other sheet. Which means that I easily can see (and count) the words that I had trouble with from the original lists. And afterwars I can have an extra look at each column in the original list to get my memory refreshed - with the added bonus that I now know the problem words. And even better: I cover up the 'foreign' columns in the original and try to reconstruct them from the translations, which can be surprisingly easy right after I have written the control list.

Method no. 3 has become my preferred method by far because it takes much less time (and ink), and during an experiment with Serbian words in July 2014 I therefore decided to do not one repetition round as usual, but three: one day, two days and 2-3 weeks after the original list. And this revealed an unexpected pattern: generally I remembered around 80& in both round 1 and 2 (somewhat lower in round 2 for subsequent experiments), and almost as many words remembered even in round 3. The surprising thing was that the overlap of forgotten words was quite low - roughly a fourth of the forgotten words between round 1 & 2. Or in other words: most of the forgotten words from round 1 weren't forgotten in round 2. Maybe they had been relearnt, maybe they just didn't occur to me in round 1 for inexplicable reasons, but overall the number of remembered words was so large that it might be better to learn some new words rather than trying to eradicater the rest group.

I did another kind of tests during this experiment: after each letter (one a day) I did a word count for that letter with a number of dictionary pages representing that letter and a similar number of pages from the other end of the alphabet. The result was quite interesting: in the 'unstudied' part of the alphabet I knew roughly a third of the word in the dictionary (a Сазвежћа with just 12.000 words), but after doing wordlists with roughly a third of the words in the dictionary the percentage went up to 66% for all words in the 'studied' part of the dictionary. So far I have not checked whether the percentage stays at this level several months later, but with the retention rate at the 3. repetition round staying put this wouldn't be an unlikely outcome.

Edited by Iversen on 25 August 2014 at 12:04am

34 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 4 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:15pm | IP Logged |

Alternatives

Of course there are alternatives to wordlists: the most extreme is the exclusive use of graded texts as the most vehement adherents of the natural method propose. I don't understand their motives, but respect their bravery. However I do understand the unorganized use of dictionaries plus genuine texts, but frankly I think there is room for improvement in that method.

Finally, there are wellstructured alternatives like paperbased flashcards and electronic versions of these, all based on the notion of 'spaced repetition': Anki, Supermemo. However I can't give advice concerning these systems because I haven't tried them myself.

Edited by Iversen on 16 September 2009 at 5:17pm

4 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 5 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:18pm | IP Logged |

Active and Passive Vocabulary

I would say that wordlists, flashcards and looking up unknown words in dictionaries all are 'active activities'. But no matter how you initially learn a word or phrase it isn't garanteed that it will be learned so efficiently that you can be sure of being able to recall it in the next relevant sitation. And that's another just way of saying that those words became part of your passive vocabulary, but not yet of your active vocabulary. To convert passive words into active ones you normally have to relearn them several times, and then you also have to use them.

As I have written in other threads my experience is that the better I know a certain language the larger my passive vocabulary will be, - but the proportion of my vocabulary that also can be used actively also goes up. In Danish, which is my native language, I could probably see myself using just about every word I know (and that's quite a lot). In Russian I know a fair amount of words, but when I write something in that language I have to use a dictionary almost at every sentence because I can't recall the words when I need them. But when I then see them again I'm quite aware that I already knew them. This happens again and again, and it clearly illustrates the nature of a passive vocabulary.

Amended quote from All I need to know is 2500 words, 18 September 2006:

If you want to know your proven active vocabulary, in principle somebody has to write down everything you have ever said (in a certain language), take everything you have ever written, grind it through the lemmatization mechanism used by lexicographers and finally subtract everything that you have forgotten so effectively that you wouldn't be able to recall it by yourself. Then add all those words that you could have used if you had got the chance. No way that you can make a rocksolid estimate of that!

Learned people have tried to quantify the written heritage of great men like Shakespeare, but I don't think anybody will do it for neither me nor the other honorable members of this forum. So we have to guess or use other methods.

After a couple of months as a member of this forum I spent a couple of hours (unwisely, maybe) on collecting every single English utterance that I had ever put on this sprawling forum. I had not been discussing cooking, African wildlife, astronomy or gardening here, and I had only very briefly commented on music, history, law and modern electronic gizmos. Nevertheless I had during the preceding two months written quite a lot (28.000 words in English) about quite a lot of strange subjects, and I had suspected that it all in all would amount to thousands of 'lexicals entries'. And then I found that after applying all the tools of the trade I had only used about 2400* different English words!

Deep frustration!

At least it makes it more realistic that you could do quite well with a limited active vocabulary in even quite demanding surroundings. Add a couple of hundred birds, plants, industrial brand names, kitchen utensils, swearwords and other essential terms, then living happily on say 2500 words suddenly doesn't seem unrealistic.

By the way, at the time the estimate of my English passive vocabulary - based on a dictionary with approx. 75.000 entries - amounted to around 35.000 words, and I could have probably boosted it even more if I had removed the taperecorder that back then was standing on top of my fattest dictionary - bigger dic, higher estimate! (se below). But does it really matter? I think that this small exercise already has shown how little of my passive vocabulary I actually use in my daily life, and this in my opinion undermines the whole concept of active vocabulary. How can you prove that some part of your vocabulary is potentially active, if you don't actually use it?

(end of text from 2009)

Since I wrote the passage above I have made a couple of experiments which have an immediate bearing on the interpretation of notion of passive vocabulary. This notion ordinarily implies that any word in your passive vocabulary (in itself a field with fuzzy borders because of guessable words) is either inactive or active, but this is already an oversimplification. Given the right hints in a conversation you may be able to remember a word which wouldn't have been accessible to you before you had been put on the right track by hearing those words. Of course there are words which are so wellknown that you don't need any help to remember them, but the fuzzy zone is of considerable size for a struggling learner. So the active status of a word is not not a boolean true/false variable, but more like a probability tied to the number and strength of your associations leading to that word.

In May 2014 I decided to do a repeat of the experiment above, which indicated that I had used a mere 2400 unique headwords in 15000 words of running text in English. This time I copied words from my Multiconfused thread only, but this time in all languages, sorted according to language. For English I stopped at 75838 words, which were divided into two corpora which after some cleansing where contained 36304 resp. 36868 words. I then used Excel to find unique forms and reduced these to something resembling headwords. The end result was respectively 3498 and 3914 headwords in the two samples, and the combined list gave 5433 unique words so there was obviously an overlap of just 1979 unique headwords - and among these you would expect to find most of the extremely common words. Or in other words: even if you learn all word in one text, the next text you read will confront you with more new words than words that already occurred in the first text (apart from a small number of words that are likely to occur in almost any normal text, like the typical 'grammar words').

But there is one aspect more: the number of unique words grew more or less proportionally with the size of the sample (including the combined sample from the last experiment) instead of flattening out somewhere. Obviously the curve must flatten out somewhere when a writer has used all his/her active words, but unless this happens at a fairly welldefined point below the number of passive number the concept of an 'active' vocabulary inside the 'passive' vocabulary is meaningless. I have so far not seen this line of investigation followed in a truly scientific report, so for the time being it can only be a hunch, but my present gut feeling is that there isn't a welldefined active vocabulary with a specific size, only an amorphous heap of words, each with some probability of being recalled under suitable circumstances.

Edited by Iversen on 23 August 2014 at 3:21pm

10 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 6 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:19pm | IP Logged |

A warning against frequency lists

Quote from Lists of high freq. words, 17 October 2007:

I'm not too fond of frequency lists because they have problems at both ends of the scale.

For the very common words it is evident that you have to learn the words, but you will see them everywhere so you don't need a list to point them out. Furthermore those words are often irregular (pronouns) or they are essential 'glue' at the syntactical level (conjunctions), so that you need more than just a nodding acquaintance with these words to use them correctly. In fact it may be difficult to translate them in isolation because their meaning is very contextdependent and therefore also very diffuse. Such words are best learnt as part of your grammar studies in combination with profuse reading and listening.

For slightly less common words the frequency lists may be relevant, i.e. words that tend to pop up here and there, but not so often that you see them all the time. Besides these words normally have a more welldefined meaning, which you can learn - but never without the risk that they are used in idiomatic expressions. The more common a word is, the more likely it is that it has some ultra idiomatic uses that you have to learn individually.

For words beyond, say, the first 1000 items on the list the frequencies are so low that it really isn't worth learning them from a list. If you have some special interest, as for instance history or music or zoology or exotic cuisine, you will in all likelihood meet the 'special' terms of your chosen interest much more often than item 1001 on a general frequency list. For instance the history buff will meet the words for different kinds of weapons, the gourmet will have to learn the names for different kinds of meat, and the birdwatcher will be confronted with the words for each and every part of a bird plus the names of typical habitats. It is however unlikely that such words will figure on any frequency list, - and if they do it will probably be due to a methodological flaw (a too small or skewed sample), or the word is on the list because of a less specialized use.

Above those first 1000 words or so you will be better served with word lists that you have compiled yourself.

Edited by Iversen on 16 September 2009 at 5:22pm

10 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 7 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:23pm | IP Logged |

Some doubts about the use of thematic word lists

Heavily amended quote from my profile thread, 09 January 2008:

For somebody who is a total beginner it is too early to think in semantic theme groups. A total beginner should first and foremost learn the 'grammatical' words: pronouns, the auxilliary verbs, prepositions and things like that, some 'common expressions' of the kind you need to keep the conversation going and just enough 'content' words to be able to formulate simple sentences. Unless you are a tourist who needs to ask for the loo then it doesn't matter too much which content words you know, because you are still not ready to engange yourself in deep philosophical discussions.

This means that word lists based on the texts you use during your first stages of learning are the most relevant, far more relevant than any lists drawn from dictionaries or thematic word lists. Word lists based on actual texts are also good for another reason, namely that you then always have seen the word in context at least once, which is a good help for the memory. This means that text based word lists can be relevant for people who can't remember words without a context, but who nevertheless note unknown words down and who might need a way to make sure that they don't forget these words again.

Word lists based on thematic lists, such as the different sections of language guides, are useful when you want to extend the vocabulary you have learnt in phase 1, - i.e. you know the word for apple, so now you want to add the words for pear, orange, apricot and cherry. However you shouldn't take all words in each and every list in one go. I.e. don't learn the names of 100 fruits and after that 100 spare parts for cars, 100 birds and so forth, but pick for instance ten very common fruits and then return to the subject 'fruits' later on, - 100 diffferent fruit names in one session will just confuse any person with a normal brain.

Until you have tried them you may think that word lists based on dictionaries only are for the real aficionados (OK, call them nerds). But when you already know some words you will soon discover that new words are easier to remember when you learn them in bulk, using some inbuilt technique for repetition. This may be either because you already have met them but just forgotten all about it, or because you can recognize the parts they are made off, or you may have seen something similar in another language. In fact some of us actually enjoy just adding word upon word from a dictionary precisely because we don't feel them as isolated words.

Personally I prefer learning in bulk from a bilingual target language dictionary, because I then see the foreign words as headwords, not as explanations or as a lot of alternative translations. Monolingual dictionaries are much less practical - the process of condensing a long explanation will disturb the 'quick and dirty' memorizing (and beginners will probably not even understand the explanations in such a dictionary).

I normally just take a random page and select maybe half the words on that page, and if there are a lot of related words I focus on the most common or the simplest of them, plus maybe one or two more - there is no need to memorize every member of the family at once.

You should generally use dictionaries with some indication of morphological classes and clear indications of idiomatic uses (such as the prepositions used with English verbs) - but not actual quotes, which tend to be too long and filled with irrelevant stuff. Even if you don't copy all of this to your wordlists it helps to see it, and you can decide to put a marker on for instance irregular verbs for later reference. But no dictionary can give you the kind of feeling for a language that you get from reading and listening to genuine texts and speech by natives. You learn the words from dictionaries as a preparation for 'real life' so that you can read and listen and think and speak without feeling that there are unknown words and holes in your vocabulary lurking at each and every footstep. And the reason to do it from word lists is that this is by far the fastest way of adding new words, - but only IF it functions for you.

Edited by Iversen on 17 September 2009 at 11:05am

6 persons have voted this message useful

|

Iversen

Super Polyglot

Moderator

Denmark

berejst.dk

Joined 6700 days ago

9078 posts - 16473 votes

Speaks: Danish*, French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Esperanto, Romanian, Catalan

Studies: Afrikaans, Greek, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Icelandic, Latin, Irish, Lowland Scots, Indonesian, Polish, Croatian

Personal Language Map

| Message 8 of 16 16 September 2009 at 5:23pm | IP Logged |

Wordcounts and active/passive vocabulary

Quote from the thread How many words do I have to learn ?, 27 April 2009:

As I have written before the number of words you actually use is much less than the number of words you potentially could use (= your active vocabulary). If you avoid complicated discussions then you probably could end up using just 5-600 words. The problem is that you don't know beforehand which words you need outside the fundamental core of 'grammar' words (pronouns, auxiliary verbs etc.), so you definitely need a larger active vocabulary.

In March-April 2009 I did a mini test for my own passive vocabulary in different languages (which of course is larger than the active vocabulary): I took a couple of midsize dictionaries for each of my languages and made an estimate based on something like 10-20 pages. I incorporated the results in my log file, and when I was through the project I listed them all in one post for comparison (NB: a newer and more comprehensive version from November 2014 including older results is found in my log-thread - and this list will kept updated).

In my earliest word counts I just calculated an estimated number of known lexemes, but later on I also calculated a percentage for each dictionary. The main reason for this is the difference in size between the dictionaries. But there is one additional rerason, namely the differences in the way languages are structured: some make concatenations (German), others are more liable to juxtapose words (English). But irrespective of the definition of 'lexeme' in dictionaries representing different languages, it must be meaningful to say that I know for instance a third of the the thing I count in a midsize dictionary. It would then be a plausible guess that I would then also know a third of the words in both smaller and larger dictionaries and dictionaries where 'compound lexemes' are listed according to different principles.

However one thing that has surprised me is that in a couple of cases I knew a larger proportion of the words in a large dictionary than in a smaller one, - you might expect the percentage to be lower with a large dictionary because it contains rare and outdated words, but many of the supposedly rare words are international scientific terms, and I know quite a lot of those. Only with extremely large dictionaries (like my Bratli Spanish-Danish dictionary or my Webster Unabridged) the percentages seem to fall - but still to a level where I recognize more words than those I find in a midsized dictionary. To boot, there are also words in small dictionaries which I don't know, and strangely enough the percentages with such dictionaries aren't nearly as high as you might have expected.

I could in principle also have tried to assess the number of words I actually might use (=active vocabulary), but that would be based almost purely on guesswork. In many cases it is already difficult to tell whether I really know a certain word from experience or just expected it to be there because it has a parallel in another language. So right now I just count my passive vocabularies, and then I'll to find a suitable setup for estimating the active part of those.

(end of quote)

Generally the results from the wordcounts in April-May corresponded fairly well with my private and subjective assessment of my level in those languages, but I got a few strange results. For instance I got unexpected high numbers in Portuguese, which I basically learnt during a short, but intensive study period in 2006 - in fact higher than in French, where I have a university degree and forty years of experience. But this is probably a result of my study methods, which even in 2006 leaned heavily towards mass consumption of words directly from dictionaries. The fact that I feel more at home in French because my horizon in that language is wider: I have read more books, seen more TV and (until recently) travelled more in Francophone countries than in Lusophone countries. This just goes to show that your vocabulary size isn't the only relevant factor in determining your level.

Edited by Iversen on 13 November 2014 at 10:34am

6 persons have voted this message useful

|

This discussion contains 16 messages over 2 pages: 1 2 Next >>

You cannot post new topics in this forum - You cannot reply to topics in this forum - You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum - You cannot create polls in this forum - You cannot vote in polls in this forum

This page was generated in 0.4688 seconds.

DHTML Menu By Milonic JavaScript

|